For flute musician, performer, and composer

Claire Chase, music has always been about discovery. Chase founded the International Contemporary Ensemble (ICE) in 2001, was named a MacArthur Fellow in 2012, and received a Champion of New Music Award from the American Composers Forum in 2015. She also began work on a 22-year-long project,

Density 2036, in 2014. The end result of the Density

project, named for flutist Edgard Varèse’s 1936 flute solo,

Density 21.5, will be, according to Chase's website, "an entirely new body of repertory for solo flute," with one performance (and subsequent release) per year until the piece's 100th anniversary. Every few years, Claire will perform every work from the Density project up until that date, ending in a 24-hour marathon performance in 2036.

Chase is currently planning 2017's iteration of the project. She's also on tour, visiting locations from Japan to Banff over the next few months. Along with Steven Schick, she'll be the Co-Artistic Director of Summer Classical Music at

Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity. We caught up with her at this year's

Big Ears Festival in Knoxville, where she played to a rapt audience at The Standard, a venue in the heart of downtown. She ended her set with Varèse’s piece, which continues to be one of the most influential musical compositions in her life. We sat down with her (and her friend, composer and multi-instrumentalist

Kyle Brenders, the Banff Centre Program Manager in Performing Arts) to talk about the Density project, her first exposure to experimental and avant-garde music, future collaborations and plans, and the state of the world.

At several points during our conversation, friends and fans of Chase came up to pass on words of praise and gratitude for her performance and her music. Many shared about how deeply she has touched their lives. Chase epitomizes the qualities of open graciousness and appreciation for her fans. For me, she is a model of how to be immersed in one's passion while still embracing full connection to the outside world.

Asheville Grit (AG): How did you first come to experimental/avant-garde music? You said during your show that you discovered the Varèse piece at age 13. How did you react to it?

Claire Chase (CC): My experience with that piece was a before and after moment of my life. My teacher brought the piece into my lesson and put it down on the stand. It was two pages of music, and I looked at it and said, "This doesn't look like music." There are lots of really low notes and really high notes, lots of swells and only one trill, and I was like, "That's stupid, where's all the fast stuff?"

And he said, "Do you want to hear it?" And I said, "Yeah I want to hear it," and he said "Ok, stand back.'" And we're in my parents' living room, this little carpeted tiny living room, and people are walking around and doing a million things, and at the same time, for the next four and a half minutes, I was completely transfixed. It was one of the most powerful four and a half minutes of my life, and I didn't know what was happening to me. I didn't know what I was hearing, I didn't know what kind of music it was, I didn't know what to call it, but the effect it had on me was profound. I was like, "Whatever this is, I want to do this. I want to learn how to do this and make music like this and have this kind of effect on other people. I want to share it." Because all of a sudden the flute was not just a flute. It was a percussion instrument. It had the power of a brass instrument, the sensuousness of the human voice, the brutal, raw engine of city sounds and sirens.

So that was when I got bitten by the bug, and it was totally visceral and emotional. I became completely obsessed with the piece and I didn't want to play anything else. My poor parents had to listen to me practice it, and then I wanted to play it at my junior high school graduation, not because I was trying to be contrarian—I didn't even know that it was avant-garde. It just, to me, was the coolest thing I'd ever heard. It was beautiful and terrifying and moving, and I wanted other people to have that experience. I thought that playing it on a football field with a bunch of jeering adolescents would be great. I was like, "I'm gonna convert them!". And I wasn't ever allowed to do that, and maybe that's for the best. But I think that if you tell an adolescent not to do something it's the surest way they'll continue to do it. I've played the piece a thousand times.

AG: I noticed that it's part of every performance and on every recording of each iteration of Density as well. Does it change for you every time you play it? How?

CC:

AG: I noticed that it's part of every performance and on every recording of each iteration of Density as well. Does it change for you every time you play it? How?

CC: The piece is really different in different spaces. It changes every year. Part of the recording project will be to have 24 albums with 24 different "Densities

," which I think will become its own album, you know, like the "Aging Density" [laughs]. The first version is from age 30, the last will be at around 60.

But it's also totally different in different spaces. It's a different piece and has different pacing if you're playing it in a black box theater or in a stadium, or in a hall like [the Standard]. I often do it either at the beginning or the end of a program, and it's much harder to do at the end.

AG: Why is that?

CC: At the end you're super exhausted, and it's actually one of the hardest pieces of flute music. It's only four and a half minutes, but it's like an opera happens in those four and a half minutes. Great pieces of music don't really have a time. You're just in them, and you're like, "Was that a blink, or was that four hours?"

Kyle Brenders (KB): It did feel longer today, and that's not a bad thing. I felt like I could be there for a long time.

AG: I had that experience, too, of getting lost in the piece and not being aware of time. How do you choose the places where you play it? Have you planned it out several years in advance?

CC: Yeah, things are planned out for the next few years, just because the conditions I'm creating in the cycle are getting more ambitious and involving more collaborators.

Density 2017 will involve hundreds of community participants. It's a 90-minute piece for solo flute, electronics, and mass participation, so it had to be planned far in advance. It will be fully staged and it's going to be like a piece of 21st-century Greek theatre.

We're about to reveal where the New York premiere will be. Our hope is that it's the kind of piece we'll literally be able to do anywhere. We could do a honky-tonk version anywhere, or a fully-produced version anywhere, whether it's a stadium or a park. We just did the first section in St. Paul with about 189 people. That was just to workshop section one, because you imagine these things and don't really know if they'll work until you get in there. So that we planned in advance. But I like to think of the Density project as the most malleable thing. This will be the first four-year retrospective, and we'll do a four-hour single-sitting marathon, first at Berkeley Art Museum in the fall, and then another one in Boston, and then, who knows? That may be something that tours and has a life, but I won't really know until I do it. The project is by design flexible and malleable, and I want to be able to do for audience of one and an audience of 10,000 and for those both to matter.

AG: So when you're getting ready for something like a four-hour—and even longer—marathon, how do you deal with performing that long? Do you have any tricks or practices you come back to?

CC: It's a work in progress, and if you think about entirety of the project, you can see that it's a long durational performance that continues into the practicing and preparing, mentally and with the instrument. I learn new things every time I do it. I do have rituals. My exercise routine keeps me in shape. Flute playing is a pretty athletic thing, but I'm growing with it.

Interestingly, the marathon part is easier. It's much easier to play in a single sitting without breaking concentration than to pause between pieces and talk. That was right for this venue and vibe [at the Big Ears show] but I so much prefer getting on stage and bringing people in, and being there for 60 minutes, for two or three or four hours. People can come in and out, but if I stay in that space I play so much better, and I think that's the essence of the project. What happens when we have 24 of those? I don't know, but what a fun thing to try to find out.

AG: What other projects do you have in the works right now?

CC: I'm working on a project with an interesting German Artist,

Jorinde Voigt. Her gallerist, David Nolan, approached me at Art Basel Miami and asked if I'd create new music in response to her large-scale drawings, which are so musical. They're essentially massive, intricate, beautiful, visceral graphic scores. I've been working with another collaborator,

Pauchi Sasaki, who is a magician of an electronics violinist, and a sound artist, and just a wizard. So she and I have been working on musical responses to these works, and it looks like it will develop into a much larger project

And there's been a bunch of stuff with ICE. We're going to Abu Dhabi in a couple of days, going to play with

Vijay Iyer, and then we'll tour in Europe. I'll be going to Tokyo to play a new concerto. I'm also working in Japan on a cool project on the work of

Pauline Oliveros. She's one of the most important people in my life. I still can't talk about her in the past tense. I just had dinner a couple of nights ago with her spouse, Ione, and we were of course talked about her the entire time. And I said, "We're both talking about her in the present tense," and she said, "It's all right, she's sitting here. We're developing a new relationship with her in another realm."

I'm working on a lot of new projects around her work, and around bringing her work and her legacy to a lot of new audiences. For this project, I will have translated a bunch from her

Anthology of Text Scores. I'll be teaching and performing them with Japanese musicians for Japanese audiences. And then a ton of other projects of Pauline's stuff will follow that, including an opera, which she didn't finish before passing. But we'll do a partial version of it, and we'll do our best to do it justice. It's wonderful how much attention Pauline is getting. I won't protest, but having known her and her struggle, being a gay woman living in the country, marching to own drum, doing her own thing, and being utterly uncompromising about her identity as an artist and her own evolution and her own track did not make her the darling of the mainstream establishment.

KB: She was the keynote speaker of the Conference of the Canadian New Music Network, and she gave a talk about her life, about how she just went ahead, just did it and followed her own path. It was so inspiring.

CC: And of course this summer I'll also be in Banff with my co-conspirator Steven Schick, who was my mentor and my hero.

AG: I've been thinking a lot about the idea of legacy, about how so many performers here at Big Ears are doing what they are here and now because of the people who came before them. Since I'm from Asheville and we're so close to the original Black Mountain College, I have to ask about John Cage and what influence he's had on you.

CC:

AG: I've been thinking a lot about the idea of legacy, about how so many performers here at Big Ears are doing what they are here and now because of the people who came before them. Since I'm from Asheville and we're so close to the original Black Mountain College, I have to ask about John Cage and what influence he's had on you.

CC: Oh yeah, Cage is grandpa! [laughs] I didn't know him personally. I never met him, so I don't have the kind of relationship I have with Pauline, because I've known her since I was a baby and I identify so much more with her work and plight. I think Cage would be the first to admit that he was influenced greatly by her and took a lot from her—some would say appropriated, and he would probably say it's all public property and ideas flow around...History was on his side in his lifetime, but there's no musician, whether they are in the practice of something very traditional or very avant garde, that isn't deeply affected by Cage whether they know it or not, by his ideas or his presence, by his generosity and, yeah, just by his way of thinking about sound.

So yeah. There's Cage, there's Bach. It's inescapable [laughs]! For Bach there's Hildegard of Bingen.

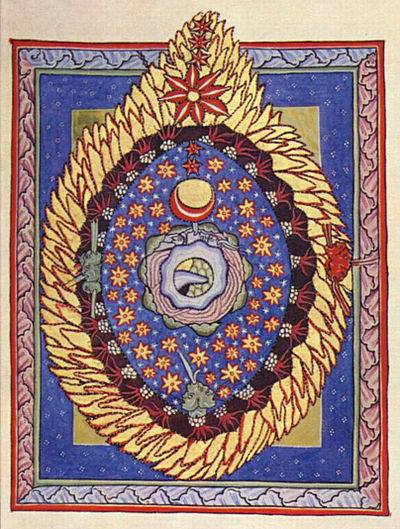

Manuscript illumination from

Manuscript illumination from Scivias (Know the Ways)

by Hildegard of Bingen (Disibodenberg: 1151)

AG: I love Hildegard!

CC: She's my girl. I am the hugest fan. The more I learn and read about her the more I love her.

The Lingua Ignota is one of the subjects of a piece I'm creating for

Density 2017, which is called "Pan," like the mythical figure of flute-playing fame, but also "pan" as the combining form for all. The language we're using is the Lingua Ignota. I may play it in the [Big Ears] Secret Set tonight at Jackson Terminal. It's super creepy: I'm screaming my head off inhaling in Lingua, and that's followed by a very melodious thing where I'll ask people to play wine glasses with me. I love when Hildegard said, "An interpreted world is not a hope."

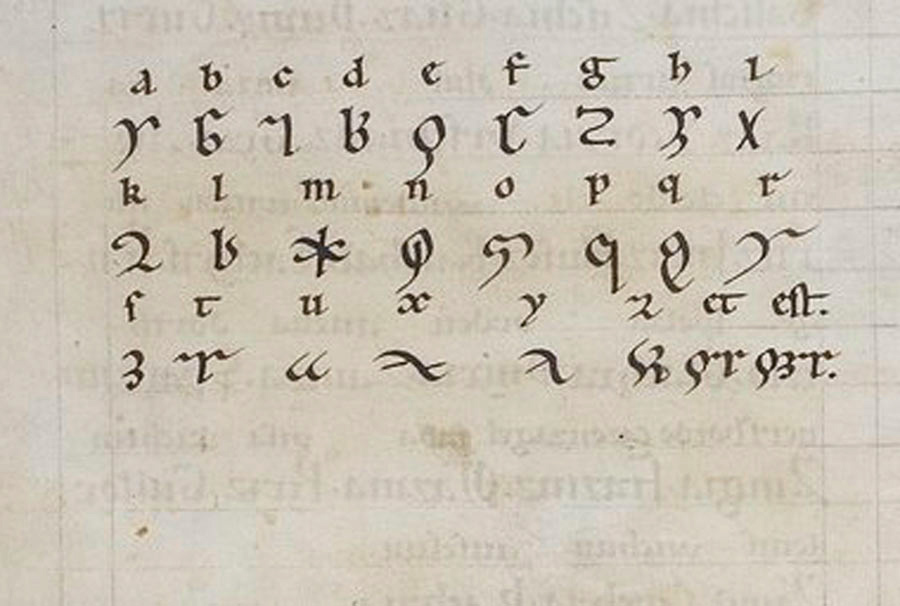

Hildegard's Lingua Ignota.

AG: What are you inspired by right now? What are you reading, watching, listening to?

CC:

Hildegard's Lingua Ignota.

AG: What are you inspired by right now? What are you reading, watching, listening to?

CC: So many things. I'm reading a lot of Anne Carson,

Autobiography of Red, and the essays and poems. I'm inside her world right now, I love it so much. And I'm rereading Emerson's essays, which I just love. I've been spending time in New England. And I've been listening constantly to music, so it's always hard to answer that question. Glenn Gould playing Bach is always on repeat; that's my morning jam. I've been listening to a lot of Anais Mitchell and Messiean. "Why Did we Build the Wall?" is so so beautiful. I've been really really inspired by Claudia Rankine. This is such a fucked up time, and I'm so tired of hearing myself complain about it. I don't want to tolerate another word that's a complaint that comes out of my mouth. It just adrenalizes us and I just want it to be about action, you know?

AG: What kinds of action are you taking?

CC: I've been really inspired by MoveOn.org and these weekly calls they organize on Sundays [

"Ready to Resist"]. It's the most brilliant thing. Every Sunday at 8 pm you send an email and they call you. It's the largest conference call. It broke the record for a conference call in January with 27,000 people, and the last one was close to 40,000.

It's an hour-long conference call. I thought I'd be done with conference calls after I stopped running an organization [ICE]. Conference calls with a ton of people was my life for 15 years, so I never thought I'd elect to be on another one, but it's the most amazing thing. It's got all the properties of a conference call you'd expect. It's awkward but so well organized, with a very clear agenda. And they do a great job in the way they curate speakers for the call. They bring in leaders of large organizations, who are professional, inspirational speakers, but also people who are 19 years old organizing their first event in a tiny town.

It's a really really cool thing, and I love it because it's totally focused on what happened in last seven days that's really positive, that made a difference. It's inspirational stories of people who are major movers and shakers and career activists interspersed with stories of first time community activists just discovering themselves and reporting what they've done. And the second half of the call is what will happen in next six, days before we get together again.

There were thousands of people on these calls. But at any point you can press *2, and you are directed to a local MoveOn person to ask a question. It's dynamic in that way. They've figured out the most beautiful participatory performance I've ever participated in, and that's what I do! I'm so interested in it. I want to get George Lewis on one of these. So yeah, you can talk to a person, to ask a question or share a comment, and it's all logged. Every 12 minutes or so they ask a question, like, "Ok, who's willing to host an event this week? Press 1 for yes and 2 for no." Then the results are aggregated, and they come back and say, "60% responded 'Yes,' and we'll be in touch to follow up."

The way MoveOn has organized it, it's so accessible. It's a way to cut through annoyance of all the complaining. And there's a lot to complain about and to be angry about. But here we have this person who's Commander-in-Chief, and all he's doing is yelling and complaining, and we're not going to get through this by yelling and complaining. Yes, we need to be on the streets. Yes, we need to be on the Face-Places and we need to be doing all the things, we need to be calling our congress-people. I was calling people backstage! But we also need to be asking ourselves what we can be doing in the next six days. Not everyone has to give up their job and join the circus right now. Some people have decided that's what they want to do, and everybody else can spend six minutes on it a day. It fucking matters.

KB: I live in the mountains, in Canada, so I have a different perspective. We bring in artists all the time, and the week after the inauguration, we had a songwriter from Nashville, Gretchen Peters. She and her husband are Hall of Fame songwriters and her son is trans. She's an old-time country singer-songwriter and she lives in a world where people around her are against her family. They were freaking out about what is going to happen. The people they sing to and write for are some of the people that voted this in and wanted it in this country. I sometimes feel like I want to say, "I told you so." 10 years ago I was doing a PhD and I wrote a paper about the music of white supremacy, and there's a record label in Detroit that sells a million records a year, and it's hate music. So the paper was about the accessibility and ease of finding this music, and that was 10 years ago.

If you go down to the root, it's the same music. Irish folk, French Italian opera. Commercialization separated people into black and white music. There's the history of America right there. Aaron Fox at NYU wrote an essay, "White Trash Alchemies and the Abject Sublime," about that euphoric feeling you get when you listen to a country song that's like, "My truck died, my dog died, I beat my wife." You feel a euphoria when listening to it. It's the abject sublime. And you can access the worst of it, the most abject, the hate music, everywhere. This hate now is more visible. I saw that coming. At the time I just tried to expose it. I was at Wesleyan, and I moved back to Canada partly because of that division between the university, where everyone's paying $35,000 a semester, and one street over where people are poor, homeless, on drugs. I saw that everywhere throughout the East Coast. It exists in Toronto, too, but with the sheer amount of people that live in the United States and the tension that was bubbling, I had to get out.

CC:

CC: This ties into Banff this summer. I was speaking with Vijay Iyer, and his way of describing the music he makes for this moment is one of the most beautiful and precise definitions I've heard: he said that we have always belonged to many different musical communities, that genre is a very recent and problematic concept and we don't need to live by it. We've been doing fine for thousands of years understanding that we are musicians, that our walls are porous. And the more porous they are, the more interesting we are, the more accelerated our evolution as musicians is, and the richer our creative lives are. Our possibilities of communicating with people who are not in our musical community but might be a part of it is higher, and the possibility that we might be a part of their community, and that our musical community might shift, is enhanced.

Things are constantly shifting; that

is the natural course of things. People say, "The center won't hold," and I'm like, "What center?" The center is our evolution, the center is actually the fact that things are constantly changing, and as artists, and especially musicians, it's our responsibility to embody that.

When people say the center won't hold, they mean center of things we're comfortable with—the large institutions. This institution of classical music is an institution of white people, and the fact that that center is not holding is the most wonderful thing. This rich history does not begin with Bach and end with Beethoven, and this is, I believe, one of the most exciting and prolific times in all of history. The state of the arts is richer, better, deeper. It's bigger and more generous than it's ever been, while the state of institutions has never been smaller and more depressing and more broken.

So what's the big deal? What do we do as artists? We get inside the institution to move it around. It's like termites and elephants. If there are more and more termites inside institutions and working with institutions to show them the way, institutions will follow artists. Sometimes it takes hundreds of years, but we're led by artists and not institutions, so there is hope. And what Vijay is doing, what we're doing at Banff this summer, is trying to dissolve the line between jazz and classical music. Vijay doesn't identify as jazz, and our program interweaves jazz and classical music. It's all just music.

KB: My teacher is

Anthony Braxton, and it's that same thing with him. In one seminar we watched

West Side Story and

Drumline. There's no division and it doesn't matter; there's something to be gained by everything. For him as an African-American from the Southside of Chicago, he has to fight not to be called a jazz musician, or a classical musician, not to just be identified as a black artist. He's always looked forward, looking to push and be pushed, to challenge.

CC: As George Lewis would say, "It's straight up Foucault." I had this conversation with

Esperanza Spalding. We're working on a project together; a new concerto with me on contrabass flute and her on contrabass and both of us on vocals and she was like, "I'm not a jazz musician. I'm so tired of the J-word."

KB: She played with

Joe Lovano 15 or 20 years ago when I was in university, and it was like I did not want to hear Joe Lovano. I wanted to know who this woman was playing the bass. I'd never heard of her.

CC: She's a magician.

* * *

Chase is on tour now and will be in Banff for Summer Classical Music from June 18 to August 12.