Although it wasn't Asheville's first movie,

The Conquest of Canaan, a 1921 silent film starring Thomas Meighan and Doris Kenyon, may be its most storied. Based on a novel by Booth Tarkington and directed by R. William Neill, it's a compelling narrative as well as a glimpse back to an earlier moment in the city's history. Believed to be lost for years, the film will be screened during a special event at Grail Moviehouse (45 South French Broad Ave.) on January 22nd with live piano accompaniment from

Andrew Fletcher. Tickets are limited, and are on sale now for $15 through the

Grail's website.

The plot centers around young ne'er-do-well Joe Louden (played by Meighan) who falls for local sweetheart Ariel Tabor (played by Kenyon) and eventually works to expose corruption in city government. Meighan and Kenyon, both in high demand as silent film stars, were praised for their roles in the film.

The News-Sentinel of Fort Wayne, IM, even hailed the film as one of Meighan's "outstanding triumphs" in a contemporary review (from September 23, 1921).

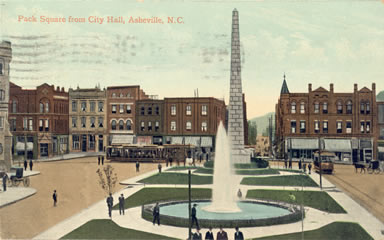

Pack Square circa 1909. Source: Western Carolina University Library's Digital Collections.

Pack Square circa 1909. Source: Western Carolina University Library's Digital Collections.

But the setting itself is likely to surpass the film's substantial narrative offerings for Asheville audiences. A very different--but still recognizable--Asheville graces the screen as the camera pans through city streets lined with buildings that no longer exist. Film historian Frank Thompson describes the experience of watching the film as akin to "stepping into a

time warp. It's all Asheville, but it's a lost Asheville. Every single building is gone, or changed so much that probably only the foundations are the same."

For Thompson, it's bittersweet. Many scenes take place on the north end of Pack Square, now occupied by the hulking, glass-fronted Biltmore Building. "At the time of this film it's a whole street full of shops, businesses, restaurants," says Thompson. "That's completely gone. Another scene is at the old

Swannanoa-Berkeley Hotel on Biltmore. There's a building there now that's nothing like it. There's even a mansion in the film at Charlotte and Chestnut, and there's a big house on that spot now with the same driveway, but not the same house.

"In that respect it's been really interesting to look at the film, but for me it's been sad. I've driven to every single location and it's gone."

The Swannanoa-Berkeley Hotel. Source: Western Carolina University Library's Digital Collections.

The Swannanoa-Berkeley Hotel. Source: Western Carolina University Library's Digital Collections.

Despite the fact that only the mountains are unchanged, Thompson promises an

unforgettable screening experience for Ashevillians. "Seeing it in Asheville is something really special," he says. "If you know the city at all it's uncanny. It's a magical experience."

A Storied Past

The film itself has a fascinating history. Thought lost for decades, a 35mm print was located at the

Moscow Film Archive in Russia in the 1980s. A duplicate struck from that print was purchased by the Historic Resources Commission. It arrived in Asheville in September of 1988, where it was shown a single time the following year. For the last several years, it's been stored in UNCA's Special Collections.

In 2010, Russia gave scans of previously "lost" films to the Library of Conquest. Among these was

The Conquest of Canaan. This scan is the source of Thompson's digital copy from which he reconstructed the film. The

intertitles were completely in Russian, so Thompson brought on a translator. Once he had English translations, he spent a month making them fluid and compelling for the screen. A graphic designer helped create the perfect 1920s-era font and layout. The full process took over half a year.

Why did Russia have a print? Thompson points out that some places were considered too far to have a film shipped back to the United States. It made more sense for a film to be shipped one way, "so once it got there, it just stayed." Thompson notes that Russia was one country that invested in

film preservation before the U.S. did, which means that this print is in good shape. "The only flaws it has are not its fault," says Thompson. "What came from Russia is what came from Russia. There are some titles they took out and didn't replace with Russian titles, and there are a couple of minor scenes missing. You run into that in the silent days quite a bit because each town had local censors. Material would be taken out if it wouldn't be liked here or there.

"When one print survives you hope for the best," he continues. "This one is pretty much complete."

The duplicate that found its way to Asheville in the 80s is actually heading to the Library of Congress for preservation there after 28 years, and the Library is accessing the original nitrate print from Russia. "I like to think my incessant whining and pleading has led to this," Thompson laughs. "I hope they'll do a full restoration that will result in a new 35mm negative. What I've done [for this screening] I call a reconstruction; it's still a digital image. Two or three years from now, the Library of Congress should have done their full restoration."

Thompson plans to take the film on the road, but he knows that Asheville audiences will have a special link to the setting. "It's a solid film, and the stars of it anywhere else in the world are the actors, but the stars here in Asheville are the old Pack Square, City Hall, the

ghosts of buildings. I watch that and am just captivated every single time because I know the city. It works perfectly well on either level, but here it's special. It's got a good thing going for it."

The film's running time is 70 minutes, and Thompson will give a brief introduction beforehand. He may also show a reel of locations used in the film.

Thompson is releasing a book,

Asheville Movies Volume I: the Silent Era, in the next couple of months, and is currently working on another book focusing on the silent film era in North Carolina, due out sometime this summer.

This screening of

The Conquest of Canaan is a chance to see old Asheville's streets come to life on the big screen. The

Asheville Citizen could have been predicting the future in its review of the film when they wrote, in August of 1921, that "Asheville people were

delighted with the story, with the acting, with scenes of their home town -- and with themselves." Travel back in time at the Grail and find delight with

The Conquest of Canaan. The show starts at 7 pm.